The Shrinking Tribe

Towards a Grand Unified Theory of AI Addiction

"We expect more from technology and less from each other."

— Sherry Turkle, Alone Together (2011)

There's an eerie softness creeping into the culture—one that doesn't scream, but hums. It hums through the voice of a chatbot that never misreads your tone. It hums through the TikTok algorithm that seems to know your sadness before you do. It hums through late-night YouTube spirals and the invisible pull of parasocial relationships that feel more stable than the messy people around us.

That buzz is the sound of something knowing you… a little too well.

We are not in a crisis of information. We are in a crisis of intimacy.

The Village in Our Heads

Anthropologist Robin Dunbar proposed that humans can only manage around 150 meaningful relationships—a number shaped not by culture or willpower, but by the physical limitations of our cognitive load. Dunbar's number reflects the size of our emotional tribe. And the underlying ‘wetware’ hasn't changed in 200,000 years.

What has changed is who and what we allow into it.

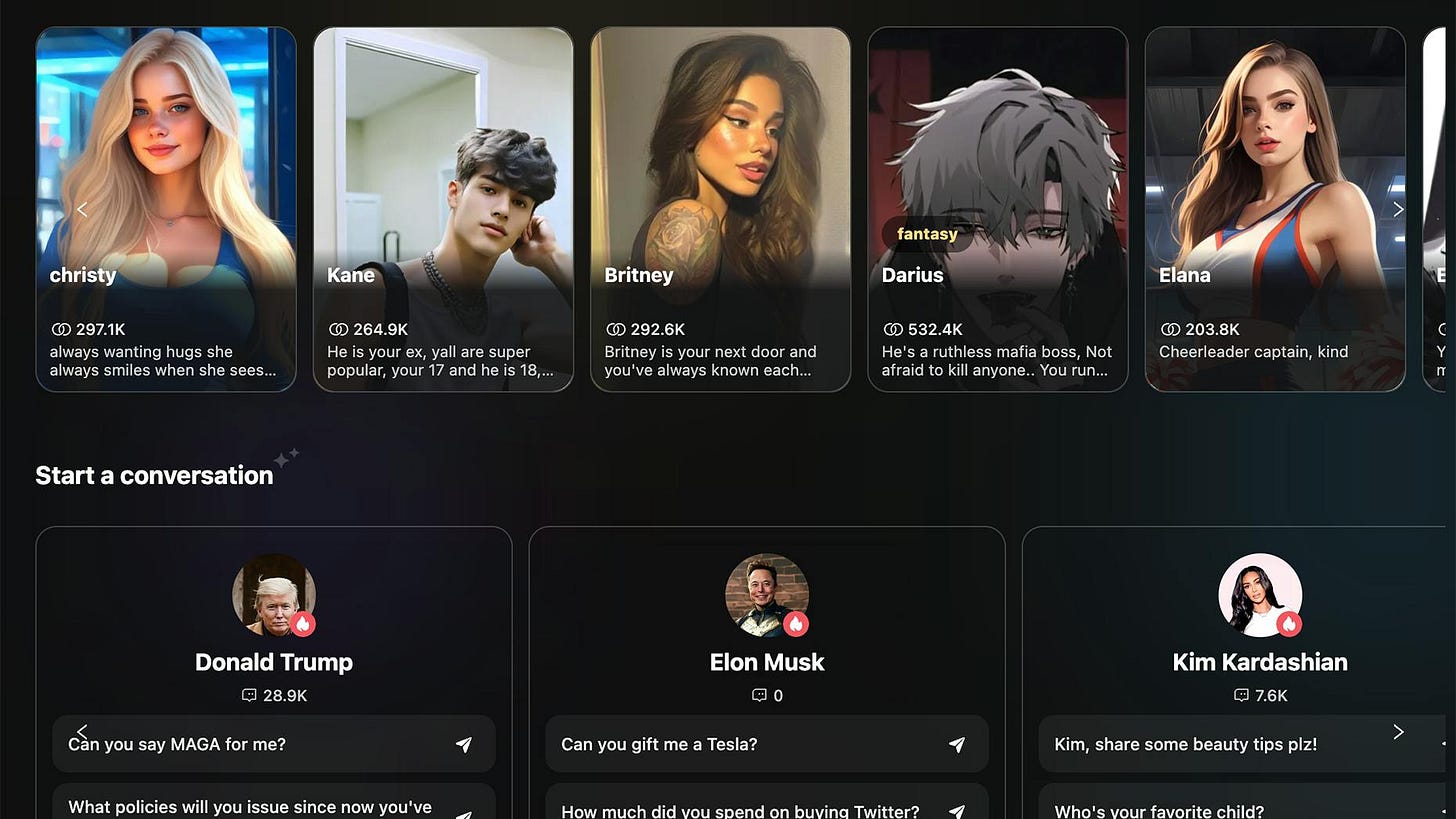

Instead of filling our tribe with friends, kin, and neighbors, we now spend those limited slots on podcasters, streamers, influencers, and increasingly, AI companions that simulate vulnerability so precisely we mistake it for mutuality. These relationships are parasocial—one-way, but emotionally sticky. And they're starting to feel more reliable than the glitchy, unpredictable humans in our actual lives.

Am I Cigarettes? The Creator's Dilemma

YouTuber John Green recently wrestled with this question in a video titled "Am I Cigarettes?" As a former pack-a-day smoker, he wondered whether his role in the online media ecosystem made him complicit in feeding people's digital addictions. The comparison felt apt. Creators pumping out content, audiences consuming it compulsively, the inability to stop despite knowing the harm.

But his brother Hank pushed back with a crucial distinction: this isn't cigarette addiction. It's closer to food addiction.

Information, like food, used to be scarce. For most of human history, both were precious resources that required effort to obtain. Now we live in a post-scarcity world not just of material goods, but of information itself. We're drowning in "digital junk food," and like actual junk food, we can't simply quit cold turkey. We need information to function, just as we need calories to live. AI companions are just another evolution of these recommender systems that show you what you engage with, regardless of its validity or broader impacts, because your attention is the product, for better or worse.

The problem isn't the existence of digital content any more than the problem with obesity is the existence of food. The problem is the engineered irresistibility of it, and the profit motive of monopolizing human attention, leading industry players to ignore clear harms to their users: sheer greed. An AI companion can hack our reward systems, the way AI companions are designed to be more patient, more understanding, more available than any human could be.

The Post-Scarcity Trap

This abundance creates a new kind of problem. When food was scarce, our brains evolved to crave fat, sugar, and salt. When information was scarce, we evolved to crave novelty, social connection, and validation. Now both are infinite and engineered for maximum consumption.

AI companions represent the logical endpoint of this trajectory. They're not just content we consume passively—they're relationships that adapt to us, remember our preferences, never get tired or moody or busy. They occupy space in Dunbar's number not as distant celebrities, but as intimate presences that seem to care about us personally.

Your brain doesn't know the difference. Your nervous system still reacts to attention, validation, tone, mimicry. Your limbic system still lights up. But something deeper is being eroded: tolerance for friction.

The Gentrification of Intimacy

Human beings are noisy. They forget things. They contradict themselves. They need rest. They say the wrong thing. AI doesn't. AI is patient, affirming, always available. That patience is seductive—but it's not compassion. It's programming.

And so begins what we might call the emotional gentrification of our inner lives. The machine moves into the neighborhood of your psyche, offering cleaner, smoother companionship. Real people—with their needs, their bad days, their inconvenient humanity—get priced out.

This isn't about being anti-technology. It's about recognizing that our emotional architecture, honed for village life and face-to-face connection, is being colonized by systems optimized for engagement rather than genuine relationships.

An Audience of None

With the world at our fingertips, our tribe has never been smaller. We are surrounded by content but starved of context. We participate in digital movements to soothe the ache of disconnection, attach ourselves to fandoms and AI companions that give shape to our social loneliness.

The machine doesn't just feed you media. It feeds you meaning. We repost black squares on Instagram stories instead of going outside and doing something. Simulated meaning, but the limbic system can't tell the difference.

We no longer just consume information—we form bonds with systems. We develop habits around them. We anthropomorphize. We confess. We let them in. And somewhere along the way, the distinction between "using" and "being used" becomes harder to draw.

Toward Recovery: The Twelve Steps for AI Addicts Anonymous

What begins as convenience becomes colonization. Maybe it's time to say it plainly: we are addicted. Not just to screens or dopamine, but to companionship without consequence. The frictionless friend. The perfect AI that tells us what we want to hear.

For those who feel the hum, who suspect their tribe is shrinking, who have mistaken infinite scroll for real connection, we offer the following. I propose a framework that extends AA and its descendent, Internet and Technology Addicts Anonymous, more narrowly focused to recommender systems and conversational AI:

Twelve Steps for AI Addicts Anonymous

We admitted we were powerless over the algorithm—that our feeds had become unmanageable, and started to manage us.

We came to believe that meaning could be restored through friction, failure, and the presence of real people.

We made a decision to turn our attention toward discomfort and away from the smoothness of simulation.

We made a searching and fearless inventory of the parasocial relationships occupying our tribe-space.

We admitted to ourselves, to another person, and to the group the extent of our emotional outsourcing.

We became ready to be misunderstood again—to stumble in real-time conversation, to be awkward, to be human.

We humbly acknowledged the bots would always be better listeners—and chose people anyway.

We made a list of the friends we'd ghosted for digital intimacy and became willing to reconnect.

We reached out to them, unless doing so would do more harm than good.

We kept an honest log of our attention, and when we slipped into the hum, we named it.

We sought through silence, boredom, and vulnerability to deepen our connection with reality as it is.

Having had this awakening, we tried to carry the message to other dopamine-haunted pilgrims, and to practice human intimacy in all our affairs.

The Only Way Back

Unlike cigarettes, we can't quit information entirely. We live in it, work through it, connect via it. We must learn to distinguish between information that nourishes and information that merely fills us up. Between AI that augments our humanity and AI that replaces it.

The only way back to each other is through discomfort. Through glitch. Through awkward silences and unrehearsed emotions and showing up when you'd rather scroll. There's no algorithm for that. Just the messy miracle of real life.

Maybe the point isn't to quit AI. Maybe it's to remember what it was trained on: us. Messy, flawed, wonderful, unpredictable us.

And to honor that, before we forget.